Key point: Courts are split over whether use of the Meta Pixel to share URLs of videos users watch qualifies as disclosure of PII under the VPPA, even when they apply the same “ordinary person” test to nearly identical allegations.

Earlier this year, the Second Circuit joined the Third and Ninth Circuits in adopting an “ordinary person” standard to determine whether a defendant’s disclosure of information constitutes disclosure of personally identifiable information (PII) prohibited by the Video Privacy Protection Act (VPPA). Although this standard initially appeared more restrictive — and thus more favorable to defendants — than the “reasonable foreseeability” standard the First Circuit adopted in 2016, recent decisions by courts within the Second and Ninth Circuits have instead revealed a split in how district courts apply this test to nearly identical allegations, resulting in different outcomes on motions to dismiss.

Overview of the VPPA

Claims under the VPPA rely on a 1988 statute that, in relevant part, makes it unlawful for a “video tape service provider” to knowingly disclose personally identifiable information concerning any consumer’s video‑viewing history. The statute provides:

“A video tape service provider who knowingly discloses, to any person, personally identifiable information concerning any consumer of such provider shall be liable to the aggrieved person for the relief provided in subsection (d).” 18 U.S.C. § 2710(b)(1).

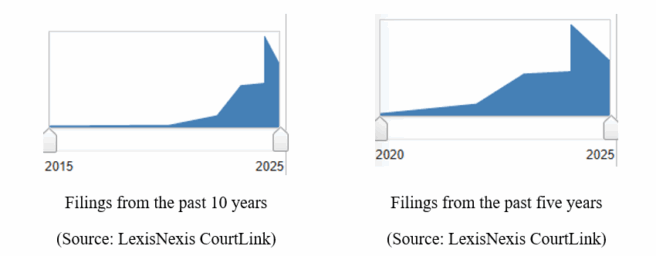

Although enacted in 1988, the VPPA was mostly dormant until the past few years, when there has been a surge in VPPA filings.

Most recently, the VPPA has been asserted against websites that use ad‑targeting cookies and tracking pixels (such as the Meta Pixel) on pages that include video content. These tools can transmit to third parties information about which pages (and videos) a user views, together with identifiers tied to that user, such as a user’s ID number for a social media network.

This theory can be at odds with the statute’s text, which was drafted when prerecorded video cassette tapes were the primary way to watch prerecorded video. The VPPA defines a “video tape service provider” as an entity engaged in the business of “rental, sale, or delivery of prerecorded video cassette tapes or similar audio visual materials,” and a “consumer” as “any renter, purchaser, or subscriber of goods or services from a video tape service provider.” It defines “personally identifiable information” to include “information which identifies a person as having requested or obtained specific video materials or services from a video tape service provider.”

Most decisions resolving VPPA claims turn on one or more of these definitions. Where the defendant directly rents or sells video content, or access to such content, many courts have found the defendant is a “video tape service provider” and that the plaintiff meets the statute’s “consumer” definition. Where the defendant’s core business is unrelated to video services, however, and the video content at issue is merely marketing for that other core business, courts are less likely to find that the parties satisfy the VPPA’s “provider” and “consumer” definitions. This is not a concrete rule, however, and there are decisions on both sides of these issues, which we will cover in our next monthly privacy litigation blog post.

A Split Has Developed Over Whether Disclosure via the Meta Pixel Constitutes Disclosure of PII Under the Ordinary Person Standard

More recent VPPA decisions have focused on whether a defendant discloses a user’s “personally identifiable information” when it uses the Meta Pixel to transmit information about when a user on the defendant’s website watches video content. Early decisions almost uniformly found that disclosure of a Facebook ID constituted disclosure of PII. Appellate courts have since taken different approaches.

The First Circuit first adopted a “reasonable foreseeability” standard, under which PII is not limited to information that explicitly names a person, but also includes information disclosed to a third party that is “reasonably and foreseeably likely to reveal which videos the plaintiff has obtained.” Under that approach, data can qualify as PII even if it does not identify the person on its face, so long as it is reasonably and foreseeably likely to reveal which videos a particular person obtained when combined with other information.

The Second, Third, and Ninth Circuits have adopted an “ordinary person” standard, under which a violation occurs only if an ordinary person — without specialized knowledge or tools — could use the disclosed information to identify a consumer’s video‑viewing history. In practical terms, the question is whether someone receiving the disclosed data, as‑is, could determine which specific videos a particular person watched.

While one might expect the dueling standards adopted by the First Circuit and the Second, Third, and Ninth Circuits would lead to a circuit split based on which standard a court applies, that has not (yet) occurred. In fact, relatively few courts have applied the “reasonable foreseeability” standard since it was articulated in 2016. Instead, a split has emerged at the district‑court level among courts that apply, or assume, the ordinary person standard (or have not adopted the reasonable foreseeability standard), but reach different results.

New York Courts Dismiss VPPA Claims Relying on Two Second Circuit Decisions

Courts in the Southern District of New York have dismissed VPPA claims that rely on the Meta Pixel to allege disclosure of PII. These courts rely on two Second Circuit decisions that affirmed dismissals of VPPA claims after finding that disclosures involving the Meta Pixel would not allow an “ordinary person” to identify the plaintiff.

For example, in an October 6 decision from the Southern District of New York, the court dismissed a VPPA claim after finding the complaint did not allege that the defendant disclosed the plaintiff’s “personally identifiable information.” The court relied on the Second Circuit’s Solomon decision, which requires that the defendant’s disclosure, “with little or no extra effort, permit an ordinary recipient to identify [the plaintiff’s] video‑watching habits” to meet the PII‑disclosure requirement. The court noted that the Second Circuit had at least twice rejected Facebook‑pixel‑based claims where the complaint did not allege that an ordinary person could see the “c_user” cookie and conclude that the string was a person’s Facebook ID (FID).

On November 13, another Southern District of New York court dismissed nearly identical claims. That court relied on both the Solomon decision and a subsequent June Second Circuit decision that again relied on Solomon and clarified that the earlier decision “focused on whether an ordinary person would be able to understand the actual underlying code communication itself, regardless of how the code is later manipulated or used by Facebook.”

California and Michigan Courts Consider Nearly Identical Allegations Under the Same Standard but Reach the Opposite Result

In contrast to the uniformity within the Southern District of New York, two courts in the Northern District of California have denied motions to dismiss VPPA claims after finding that disclosure via the Meta Pixel satisfied the PII‑disclosure requirement under the ordinary person standard. Critically, the Ninth Circuit — in which the Northern District of California sits — has adopted the same ordinary person standard as the Second Circuit and the Southern District of New York courts discussed above.

On October 7, a Northern District of California court first noted that disclosure of Facebook IDs “beg[s] the question of whether an ordinary person can discern personal and identifying information about a consumer from these IDs, whether by accessing their Facebook page that contains such information or otherwise.” The court then found that question moot because the plaintiffs alleged the defendant disclosed the plaintiff’s “full name, email address, and the title of the video she viewed,” which the court concluded would allow an ordinary person to discern the relevant information. The court also stated that “what information the Meta Pixel transmits to Meta — whether a readily discernable name and email address, or a numeric Facebook ID — is a question of fact not yet ripe for review.”

On October 20, another Northern District of California court rejected a social media company’s argument that any information disclosed through its pixel about the plaintiff’s viewing history was “paired with voluminous other information” such that an ordinary person would be “unable to sift through the morass of data to find the pieces that identified [the plaintiff] and her video‑watching behavior.” The court held there was nothing in the VPPA that “suggests that a defendant can escape liability by disclosing such information in a format that makes it less likely that an ordinary person receiving the information would actually use it to identify an individual’s video‑watching behavior.”

A Western District of Michigan court, which has not formally adopted either the ordinary person or reasonable foreseeability standard, also issued a decision consistent with the two Northern District of California decisions. Although the court declined to adopt the “ordinary person” standard as the governing test — reasoning that it impermissibly imports an intent requirement not found in the statute — the court went on to find that even under the ordinary person standard the plaintiff had adequately alleged disclosure of PII. The plaintiff alleged that anyone could simply type a Facebook ID into a web browser and locate the corresponding Facebook profile (and thus the user’s real name). The court concluded that “even if the Court were to adopt the ordinary person standard as to the type of information, there is no reason to apply it to the format of the information. For example, a defendant cannot escape VPPA liability by simply sending the information in encrypted form, even though no bystander would be able to identify a video title just by looking.”

Both the October 20 Northern District of California decision and the Western District of Michigan decision are seemingly at odds with the Second Circuit’s June decision, which held that the ordinary person standard requires such a person “be able to understand the actual underlying code communication itself.”

Resolution of this split is unlikely in the near term, as neither of the Northern District of California decisions has been appealed as of today. And there is no indication that the Supreme Court will weigh in on the VPPA any time soon. Indeed, on December 8, 2025, the Court denied a petition to hear an unrelated VPPA case from the Second Circuit. (In contrast to the PII‑disclosure decisions that favored defendants and are discussed above, that decision favored plaintiffs by holding that an individual who rented, purchased, or subscribed to any goods or services — not just audiovisual materials — from a video tape service provider met the definition of a “consumer” under the statute.)

Practically, these decisions suggest we are unlikely to see a decrease in VPPA litigation any time soon. To help guard against VPPA claims, companies that offer audiovisual materials should carefully examine what tools they use on any website that provides users access to those materials, including whether pages with video content use third‑party pixels and what information (such as video titles, user identifiers, or email addresses) those tools transmit to third parties. Companies should also consider what law and venue they select in their website terms of use, as these decisions show that where the case is heard and what law the court applies may matter greatly. If you would like to discuss these issues with a Troutman Pepper Locke attorney, please reach out.